Crystal structures for capturing carbon dioxide

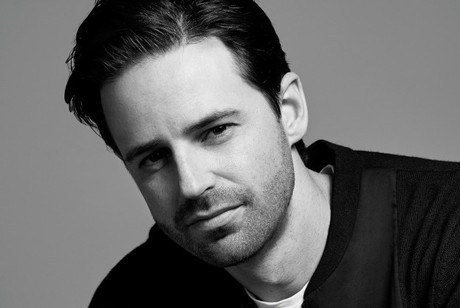

As part of a program to encourage young people into STEM careers, CSIRO is promoting seven of its top young researchers who are working on breakthrough technologies. Among the ‘CSIROseven’ is UNSW alumnus and Prime Minister’s Science Prize winner Matthew Hill, who is investigating materials that could capture and store carbon dioxide.

“40% of the energy used by large industry is used to separate one thing from another,” said Hill. “The list is endless: separating bacteria from household water, separating crude oil into usable fuel, or separating minerals into copper and aluminium for our plumbing pipes or household appliances.

“These processes are happening every day in every country, sending vast amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.”

Hill specialises in creating metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) — small crystal structures which resemble sugar or salt crystals but are 80% empty on the inside. Described by Hill as “the world’s most porous material”, MOFs are littered with nanometre-wide holes which enable the material to act like a sponge. As a result, said Hill, “one gram of MOF crystals has a surface area of over 5000 m2” — the equivalent of a football field.

MOFs have many possible applications for manufacturers and processing plants, said Hill: “For example, if you put the powder in a tank it can store many more times than gas in the same place, which saves on energy used for compression for that tank.

“Another way they could use it is that we have designed MOFs which are specific to storing vast amounts of carbon dioxide, which could be used then to absorb all the dangerous gaseous waste from the factories.”

In a collaborative project with a team in Colorado, USA, Hill used MOFs to create a filter for capturing carbon at an industrial plant. He explained, “We experimented with putting the crystals into layers of plastic polymers, essentially making filtration layers that can be connected to a pollution stream.

“About a month later, the layers were still working. It turns out the polymers bonded to the crystals, essentially making a new material that will last for a few years instead of a few weeks, which drives down the cost and makes this a much more viable option.”

For more information on Hill, and the other members of the CSIROseven, visit http://seven.csiro.au/.

PakTech moves into the Australian market

The recyling company will team up with local drinks retailer Endeavour Group, with plans...

Govt sustainability initiatives welcomed by Engineers Australia

The Circular Economy Ministerial Advisory Group Interim Report and the Environmentally...

Circular economy experts to gather in Sydney

Australian and European leaders in sustainability will come together in Sydney on 9 May for the...